CLAIM: Zimbabwe is a Christian Nation

SOURCE: Vice President Constantine Chiwenga

VERDICT: False

The question of whether Zimbabwe is a Christian country or not, is not new. It comes up regularly, like clockwork, whenever issues of morality, women’s dressing and, of course, sexual orientation are discussed.

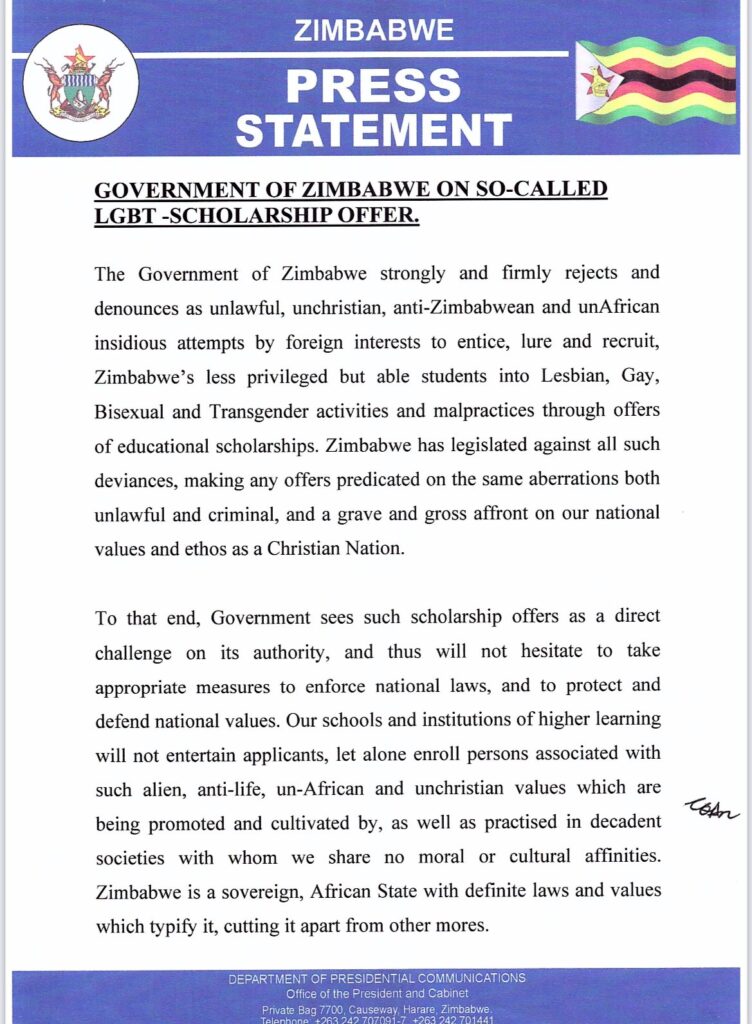

In recent days, the question rose to the fore once again, following a statement by the country’s Vice President, Constantine Chiwenga, on a scholarship targeted at LGBTI students.

In the statement, among other claims, the VP states that, ‘Zimbabwe has legislated against all such deviances, making any offers predicated on the same aberrations both unlawful and criminal, and a grave and gross affront on our national values and ethos as a Christian Nation’.

The statement was carried by the national Zimbabwe Broadcasting Corporation, here; the Information ministry, here; and the President’s communications department, here.

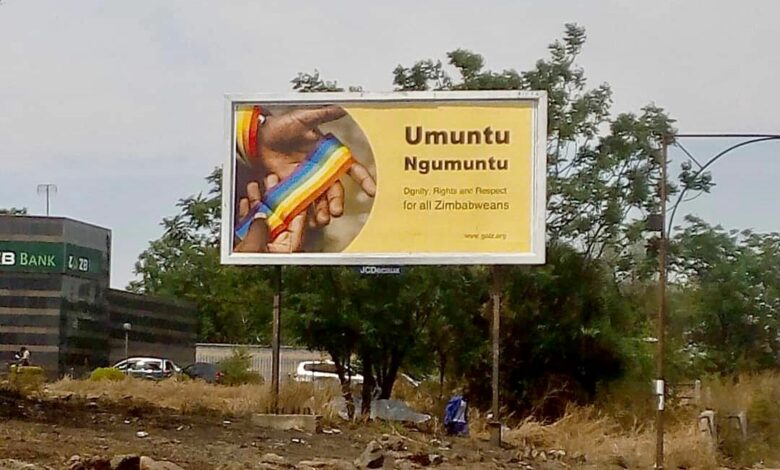

The seemingly ‘offensive’ offer is a scholarship targeted at disadvantaged LGBTI young people.

According to the call for applications, ‘The Munhu Munhu! Scholarship programme is created to provide financial support to Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Intersex and Queer individuals between 18 and 35 years of age who are pursuing a university degree in Democracy, Governance, Justice, Human Rights and Conflict Resolution studies. Through this scholarship, LGBTI youth can apply for funds to pay for educational-related expenses towards a degree from any Zimbabwean State University’.

In response, a number of social media accounts claimed that indeed Zimbabwe is a Christian nation.

One user, here, posted, ‘Thank you for upholding bible principles on this. Every good act regardless who has done should be applauded (sic)’.

Another user claimed that, ‘Zimbabwe is indeed a Christian country. That definition is drawn from percentage population of christians compared to other religions (sic)’.

A Christian nation or a nation of Christians?

The phrase ‘Christian nation’ has been called an ambiguous term. Scholars have said a Christian state is not easy to define, but is perhaps one where the public, legal and constitutional institutions are “Christian”.

When it comes to citizen rights, however, popular opinion is not a matter of legal prescription. Popular consensus can change at any time. Therefore,some argue that a Christian nation which depends on the existence of popular concensus is an elusive thing. Such a definition of “Christian nation” is entirely political, not legally based.

While it can be factually claimed that the majority of Zimbabweans self identify as Christian, does that mean that the country itself is Christian?

The questions, therefore, are: is there anything in the Constitution that gives special treatment or preference to Christianity? Did the writers of the Constitution believe this or intend to create a government that gave special recognition to Christianity?

Freedom of Conscience

As a matter of law, the constitution, Zimbabwe is a secular country.

In a secular society, the powers of the church and the state are separate. Basically, this means that the state’s governing cannot be the result of the policies and beliefs of any organised religion and that no religious leader has automatic political authority. It also means that no person has to answer to any governmental authority for his or her religion. For example, one can run for a political office no matter what their religious beliefs are.

In a secular republic, people are free to practice religion or non-religion in peace; church and state are separated; people of differing faiths are treated equally before the law; and religious tests and oaths are not required to vote or hold office.

While some have used the Constitutional preamble as proof that Zimbabwe is a Christian nation, nowhere in the document is Christianity or Jesus Christ mentioned. The preamble states, ‘And, imploring the guidance and support of Almighty God, hereby make this Constitution and commit ourselves to it as the fundamental law of our beloved land’.

It refers broadly to ‘Almighty God’ without narrowing it down to a particular faith.

Freedom of religion and freedom of conscience are mentioned more than once in the Constitution.

Section 3(2)(i)(1) states that, ‘The principles of good governance, which bind the State and all institutions and agencies of government at every level, include recognition of the rights of ethnic, racial, cultural, linguistic and religious groups’.

Section 60 comprehensively deals with freedom of conscience:

(1) Every person has the right to freedom of conscience, which includes—

- (a) freedom of thought, opinion, religion or belief; and

- (b) freedom to practise and propagate and give expression to their thought, opinion, religion or belief, whether in public or in private and whether alone or together with others

Some Zimbabweans have argued that the country is Christian since oaths are made on the Bible.

One account posted, ‘Zimbabwe is a Christian country, why do our presidents swear holding th bible? Since 1980 bob inaugural, he had a bible’.

Another claimed that Zimbabweans ‘swear on the Bible’ which makes Zimbabwe ‘a Christian state with Christian values’.

Individuals like former Harare legislator Munyaradzi Gwisai, have previously succeeded in refusing to take an oath over the Bible, as is their right.

Swearing on the Bible is not mandatory. Section 60 (2) specifically deals with the taking of oaths stating that, ‘No person may be compelled to take an oath contrary to their religion or belief or to take an oath in a manner that is contrary to their religion or belief’.

Conclusion

Zimbabwe is unlike countries like Zambia. Zambia’s then president declared the country a Christian nation in 1991. This was legalised in 1996 through a constitutional amendment declaring the Republic ‘a Christian nation while upholding the right of every person to enjoy that person’s freedom of conscience or religion’.

While Zimbabwe can be said to be a nation of self identified Christians, the claim that it is a Christian nation is false. The Christian nation tag, which often makes an appearance when issues of morality are discussed, is problematic in that it limits public discourse and channels it in a certain direction, when in actual fact, it is a false claim.