CLAIM: 2,500 women die giving birth each year.

SOURCE: Hopewell Chin’ono

VERDICT: False

Despite alarming claims circulating on social media, the true picture of Zimbabwe’s maternal mortality crisis is far more complex.

The claim around maternity theatres, ‘Zimbabwe’s biggest hospital has only one maternity theatre, built in 1977, and as a result, 2,500 women die giving birth each year’ is one that journalist Hopewell Chin’ono has been making for at least three years now.

In a post from 9 months ago, he says that he has been talking about maternal mortality and the unavailability of maternity theatres for the past five years.

The posts can be found on different social media platforms: X, Facebook and Instagram.

On 2 June, 2022, he posted, ‘I always talk about Harare Hospital having only ONE maternity theater!

Another central hospital, Chitungwiza Hospital, has only ONE maternity theater which can only allow 2 concurrent operations. For all other operations, it also has only ONE operating theater.

What a mess!! 2500 Zimbabwean women die every year giving birth due to ZANUPF’s failure to build theaters.

It only costs US$37,000 to build a hospital theater!’.

In a recent post, he writes, ‘Zimbabwe’s biggest hospital has only one maternity theatre, built in 1977, and as a result, 2,500 women die giving birth each year. It costs only US$37,000 to build a maternity theatre’.

In this fact check, we look at the claim: Zimbabwe’s biggest hospital has only one maternity theatre, built in 1977, and as a result, 2,500 women die giving birth each year.

The biggest hospital in Zimbabwe is Parirenyatwa group of hospitals. It’s maternity department is the Mbuya Nehanda Maternity Hospital.

Maternal Mortality

According to the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), maternal mortality ratio is estimated at 363 per 100,000 live births. In its 2023 Annual report, it states that ‘health service coverage, particularly in remote and urban poor areas remains low due to weak and underfunded health systems and insufficient human resources, impact of health outbreaks, harmful social norms, including religious beliefs and practices that exclude women and girls’.

The UNICEF figures are derived from the 2022 Census. The Census showed that there had been 1,589 maternal deaths in the year under review against 437,478 live births. The national maternal mortality rate is, therefore, 363 per 100,000 live births. It is highest in the Midlands at 425 and lowest in Bulawayo at 249.

Maternity theatres vs Maternal Mortality

In his claim, Chin’ono says the women are dying as a result of lack of theatre facilities (Mbuya Nehanda having only one functional theatre, according to him).

Would having more maternity theatres lead to less maternal deaths? Research shows that it’s more complicated than that.

According to a research study published in October 2022, the commonest groups of maternal mortality during the period 2011–2020 were hypertensive disorders, obstetric haemorrhage, pregnancy-related infection, and pregnancies with abortive outcomes.

The results were similar to the ones from a previous study. The 1993 study had shown that haemorrhage and sepsis were the leading direct causes of maternal mortality while malaria was the leading indirect cause in the rural setting. In the urban setting, eclampsia, abortion and puerperal sepsis were the leading causes of maternal deaths.

More interesting in this study were findings on the role of social support on good or bad outcomes in pregnancy. It was found that all situations associated with diminished, or absent social support, that is, being single, divorced, widowed, one of several wives, cohabiting, or self-supporting carried an increased risk for maternal mortality, especially in the rural area.

Age > 35 years and parity > 6 were significant risk factors for maternal mortality in the rural setting, whereas bad reproductive history with reported stillbirth or abortion constituted a high risk both in the city and in the rural areas.

Another study from 2022, cites brain drain as a contributory factor to maternal deaths, ‘Direct causes are continuing to contribute significantly to maternal deaths because of the ever-present threat of brain drain where skilled healthcare workers migrate to better-remunerating countries’.

Apart from the brain drain, Zimbabwe maternity hospitals have also seen ‘intermittent supplies of life-saving resources, such as blood products for obstetric haemorrhage, oxytocin – the standard uterotonic drug for managing the active third stage of labour and treating patients with post-partum haemorrhage. Similarly, stock ruptures of magnesium sulphate for eclampsia and anti-hypertensive medicines have been reported from time to time’.

According to the study, sustained investment in the supply of these life-saving drugs and resources is required to reduce deaths from direct causes; ‘Addressing obstetric haemorrhage would reduce deaths from direct causes by a third while addressing obstetric haemorrhage, abortion and hypertensive diseases would reduce deaths due to direct-causes by four-fifths. Thus, improving the coverage and quality of maternity care targeting these three causes remains a priority. Despite the presence of maternal waiting shelters in health facilities, women continue to experience significant first, second and third delays from various controllable factors, such as long distances to the nearest health facility and significant delays in getting transport to referral centres, coupled with human resource and commodity challenges at the referral centres’.

Delays in Performing Emergency Caesarean Sections

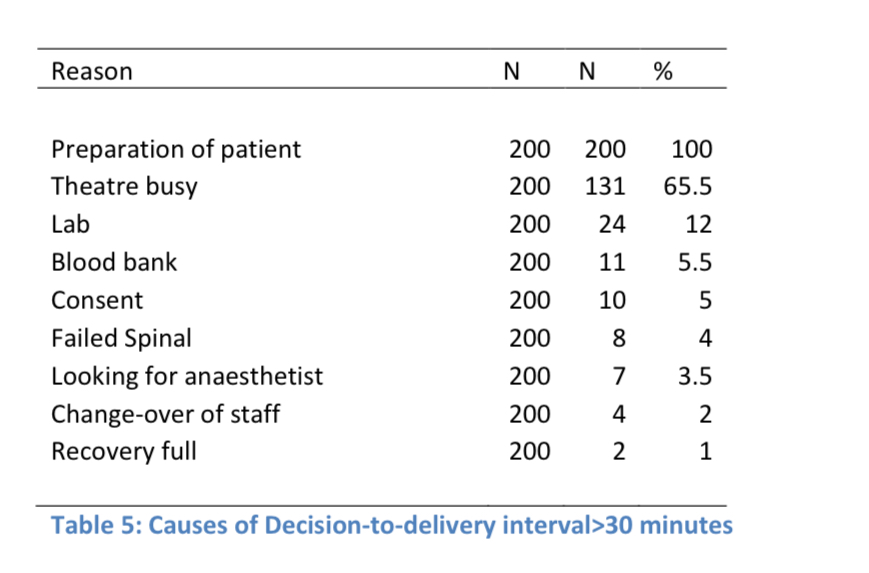

In relation to maternity theatres at Mbuya Nehanda Maternity Hospital, an academic study was carried out in 2015 looking at ‘Delays in performing Emergency Caesarean Sections at Harare Maternity Hospital and Mbuya Nehanda Maternity Hospital – Causes and Outcomes’.

The study concluded that, among other things, delays in carrying out emergency c-sections were caused by delays in the pre-operative preparation for theatre; the theatre being busy a the time the decision for ECS was made; delays in the laboratories; delays in accessing blood or blood products; anesthetic delays; staff changeover; and recovery ward being full.

The study concluded that these two maternity hospitals were indeed, operating beyond their capacity for provision of Caesarean sections. One of the recommendations of the study was that the hospitals have staff on standby that can be called in when there is need to open a second operating theatre after hours.

Conclusion

The claim that ‘2,500 women die giving birth each year’ has been rated false. The maternal mortality rate has gone down. The latest statistics have 1,589 deaths, not 2,500.

The rest of the claim is a bit more complicated. Are women dying as a result of the hospital having only one theatre? Research shows that it is more nuanced than that. While having only one theatre is a challenge in carrying out emergency c-sections, most of the maternal deaths are not as a result of only not having theatres. It’s a combination of also not having enough personnel, blood or drugs. Addressing obstetric haemorrhage would reduce deaths from direct causes by a third while addressing abortion and hypertensive diseases would reduce deaths due to direct-causes by four-fifths.

This Fact check was produced with the support of FullFact AI. The AI identifies potential claims for fact checking.